“If you were transported from modern Cambridge to Regency Cambridge, the first thing you would notice is how busy the river is. Nowadays it is rather pretty and has gentle punts on it, but Gregory would have seen it literally packed with boats delivering supplies to the growing town.”

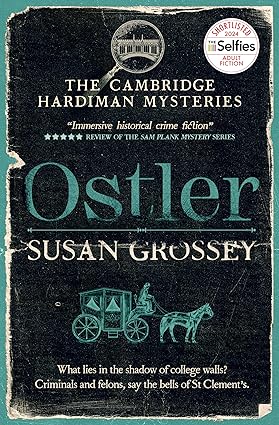

WHAT: “It’s the late Regency period in Cambridge, and fine wines and precious artworks are disappearing from St Clement’s College. But just who is responsible, and how far will they go to keep their secret?

After the horrors of the Napoleonic Wars, ex-soldier Gregory Hardiman is enjoying the quiet life of an ostler at a Cambridge coaching inn. But when the inn’s cook is found drowned in the river in the spring of 1825 and his distraught widow pleads for help, Gregory finds himself caught up in the unexpectedly murky world of college life in the town. He navigates uneasily between the public world of the coaching inn and the hidden life behind the high walls of the college. And when a new law requires the university to create a cadre of constables, will Gregory take on the challenge?”

WHO: “For twenty-five years Susan Grossman ran her own anti-money laundering consultancy. In 2013 she published ‘Fatal Forgery’ – a mystery focused on the case of a historical real-life Regency banker. Her narrator, a well-meaning, slightly crusty, deeply honourable magistrates’ constable called Sam Plank, would return for a further six novels.

In 2023 Susan released the first of her Gregory Hardiman series set in Regency Cambridge where she herself had been a student.”

MORE? Here!

Why Ostler?

While I was writing my London series – narrated by magistrates’ constable Sam Plank – I started to wonder whether my hometown of Cambridge had had a similar, experimental period of policing. When I discovered that in 1825 – right in the middle of my favourite decade – parliament had passed a piece of legislation called the Universities Act, permitting the universities (at the time, only Cambridge and Oxford) to appoint their own constables, my fate was sealed.

However, being a university constable was only a part-time job: six o’clock to ten o’clock, about five nights a week. No man could have survived on those wages, so I had to give my constable a day job. I wanted him to be able to move freely about the town and to know people at the university – and then I read about ostlers. They look after horses at the inns, and are usually the first to hear all the gossip – and that seemed an ideal choice.

When did you first “meet” Gregory Hardiman? Did he arrive in your mind’s eye all at once, or did a portrait of him establish one layer at a time? Is he based on or inspired by a particular individual?

The first thing I chose was his name. I knew I wanted a fish out of water – a country lad living in a town – and Hardiman was a common Norfolk surname at the time. I then wanted to hint delicately at another of his outsider characteristics: his religion. And Gregory is a popular Catholic name…

I was worried that Gregory would end up a carbon copy of Sam Plank (whom I loved), so I wrote down a list of how he could be different. Sam is married, so Gregory is not. Sam spent his whole life in London, so Gregory has travelled: I put him in the army, and he spent time in Spain, Gibraltar and Australia. And then I realised I had a big problem: I know nothing of military history. I was moaning about this one day during the lunch-break at court (I am a magistrate) and in one of those serendipitous moments of life, my fellow magistrate said that he was an expert in Napoleonic history and would be happy to devise a service history for Gregory! He has done that, and I stick to it like glue.

Finally, Sam is rather vain, so I wanted Gregory to be the opposite. In fact, I wanted him to be ashamed of his appearance, so I decided he should be disabled in some way. I initially thought of making him an amputee – very common in the period, with old soldiers – but of course that would mean he couldn’t be a constable, as they had to be physically fit. I eventually lighted on a large facial scar, which does not affect his health but makes people react to him.

Hardiman is an instinctive and experienced horse handler. Is that something you know about, or something you’ve had to learn? How would Hardiman judge and asses your horsemanship?

I lived in Newmarket – the home of horseracing – for five years when I was a child, so I know a little of the expensive end of horse ownership. And I know that horses are skittish and intelligent. But I have no natural skill as a horsewoman and now avoid riding at all costs after being rolled on by a fat Thelwell pony when I was nine! Thankfully, I am friends with another self-published author who is a horse-owner and knows everything I could possibly ask her about the care and management of horses – and I run every horse-based scene past her for approval. Hardiman would laugh at how uneasy I am around the animals that he loves!

The Hardiman mysteries are set in Regency Cambridge. What sights, sounds, and scenes should be included in the discerning Time Traveller’s itinerary? Where would you recommend staying overnight?

The second question is easy: you should of course stay at the Hoop Inn, run by the ambitious William Bird, and where ostler Gregory Hardiman will take excellent care of your horse. If you were transported from modern Cambridge to Regency Cambridge, the first thing you would notice is how busy the river is. Nowadays it is rather pretty and has gentle punts on it, but Gregory would have seen it literally packed with boats delivering supplies to the growing town. The boat folk were hard-working and coarse, and their shouts as they steered through the water-based throng would have been heard all over town.

You would also notice the stink of the town: the King’s Ditch (now thankfully covered up and superseded by modern sewers) ran right through the middle of town. The town would have been much darker at night – electric street lighting came only to a couple of streets in the 1820s – and bickering over whose responsibility it was to keep the streets clean and safe was almost a full-time occupation for the Mayor of the town and the Vice-Chancellor of the University. And a visit to the daily market was a must: much larger than it is now, and with a huge range of goods brought in on those boats, Cambridge’s market was famous for miles around. Particularly popular was the local butter, which was sold by the yard.

Who are the authors and sources you most rely on while recreating Regency Cambridge? Have you made any deliberate departures?

It has been hard to find many contemporary descriptions of Cambridge – the two main diarists were Henry Gunning (who wrote up to 1820) and Josiah Chater (writing in the 1840s). And very few people at all have written novels set in the 1820s – which is partly why I love it so! But that’s not to say I have been without original sources. I rely heavily on archives of the two newspapers at the time: the conservative Cambridge Chronicle and Journal (which offered no editorial comment at all) and the left-wing Independent Press (which offered perhaps too much). And – as always – local historians and librarians are an astonishing and generous source of information, no matter how obscure the question.

And no, I am very careful not to make any deliberate departures. One of the joys for me of writing historical – rather than contemporary – fiction is the puzzle of having to fit my made-up story within the known confines of history. I cannot alter something that happened or existed just because it does not fit my story; rather, I must alter the story so that it works. As I say, it’s sometimes a puzzle, but one that I love solving.

Has diving deep into Regency Cambridge shifted, altered, or enhanced your perspective on today’s Town and Gown? Is there something they got right that we are getting wrong?

Interestingly, the year I am researching and writing about now – 1827 – was the year of the first acknowledged Town and Gown Riot, on 5 November. But I am not yet sure how that will affect my story, with Gregory being a university constable while having many friends in the town. What is clear is that the two halves of Cambridge life have always found it difficult to understand each other. I have to say that my sympathy in the 1820s is with the town, because the University was so parsimonious and condescending when it came to paying its (agreed, fair) share of lighting, sewage and cleaning bills. Indeed, when I look at college accounts from the period, it seems that the colleges spent most of their money on coal and alcohol, to keep warm and drunk in the frigid Cambridge climate!

How does writing Gregory Hardiman’s Cambridge compare and contrast to writing Sam Plank’s London?

In some ways, it is easier to write about a smaller, more distinct community – London was (is!) such a vast and sprawling and cosmopolitan place that you have to pick only a small element to concentrate on. I feel I have more of a general grasp of life in Cambridge, as it is a more manageable size. That said, I can feel myself getting completist about it and wanting to know EVERYTHING about Cambridge in the 1820s, which is of course impossible.

When I was writing the London series I was fierce with myself about visiting every location that Sam went to, and – where possible – following the routes he took. We called this Walking the Plank! I used to book days in my diary, go down on the train, and just walk and walk and walk. All of this is much simpler now that I am setting books in Cambridge; if I want to check a location, I can just whizz out on my bike and get my answer within minutes.

You’ve had a rather interesting pre-literary career. Where on the journey did you turn around and say, “I really ought to put this in a book?”

For twenty-five years I ran an anti-money laundering consultancy, advising banks, accountancy and law firms, trust companies, casinos, estate agencies and the like on how to spot and avoid criminal money. But I read English at university, and I always suspected that one day I would want to try and write a novel. When that urge became irresistible (and I thought, if not now, then when?) I realised that I had become obsessed with criminal money, and that it would make a great angle for a crime novel. I published my first eight novels while I was still working full-time, and it was such fun to escape into the past but armed with my understanding of criminal attitudes to money. Of course, in the 1820s they hanged fraudsters…

You self-publish your work. How are you finding that process, and what’s the biggest thing you’ve learnt that you wish you’d known on Day 1?

I should say that I did not choose to self-publish my novels. Once I had finished the first Sam Plank book Fatal Forgery (although at the time I did not realise it was the first book – I thought it was the only book!) I submitted it to nine agents and publishing houses. They all replied in the same vein: it’s a good story, well-written, but we can’t sell it because no-one is interested in financial crime. I disagreed – remember my obsession? – and as I had already self-published dozens of non-fiction books in my working life, I decided to self-publish the novel. And that was it: I never tried again with the agents or publishing houses. I enjoy the process of self-publishing, which has changed and improved immeasurably over the years. And I like feeling that each novel is all my own work: I write it, produce it and sell it.

As for what I wish I had known on Day 1, well, it’s that nothing is forever. You can always change things: pressing the big red Publish button is not the end of the world. You can upload a new file, you can change the cover, you can publish via a different system. All of that would have made it less scary and more fun – much more like it is now!

What are you currently working on?

I am currently writing Gregory 3, which I promise you will have a better title by the time it appears in early December. It is set in 1827, and touches – among other things – on silver mines in Bolivia, balloon rides in Cambridge, and quack remedies in London.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ? FOLLOW US ON TWITTER! OR SIGN UP TO OUR MAILING LIST!

You must be logged in to post a comment.