“How do you express his executive leadership? It’s much easier to talk about the night he spent with Churchill or the meeting he had with Stalin.”

Harry Hopkins (1890–1946) trained as a social worker. He rose to prominence administering the work relief program in New York, where his tenacious efficiency brought him to the attention of Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When FDR won the White House, Hopkins was presented with opportunities to put his knowledge and experience to use on an even larger scale. An one of the architects and implementers of the New Deal, Hopkins grew the Works Progress Administration into the largest, most ambitious, and arguably most successful program to put Americans back to work, thus countering the effects of the Great Depression.

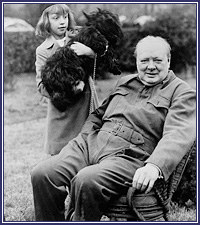

As the President’s chief diplomatic adviser and wartime troubleshooter, Hopkins oversaw billions of dollars of Lend-Lease aid to America’s Allies. His intimate partnership with Roosevelt – Hopkins actually lived at the White House for three and a half years from 1942-1944 – enabled him to build close working relationships with Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, and General George Marshall. Churchill was to write of Hopkins, “His was a soul that flamed out of a frail and failing body. He was a crumbling lighthouse from which there shone beams that led great fleets to harbour.”

Author David L. Roll was educated at Amherst College and The University of Michigan Law School. After more than 35 years as a partner at international law firm Steptoe & Johnson LLP, he founded the Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation serving as its Managing Director from 2006 to 2008. Roll is presently under contract to write a new appraisal of General George C. Marshall.

The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler (published by OUP USA, April 2013). To find out more click here.

Why Harry Hopkins?

I ran into him when I was writing an earlier book, and I saw, I got a glimpse, of how he operated. It was a night (in about May of 1942) that he was with Winston Churchill at Chequers. It was the middle of the night. They were (as usual) having a beverage or two and a cable came in to Churchill from India. It announced that Louis Johnson and Churchill’s envoy (Sir Stafford Cripps) to India had reached an agreement with Jawaharlal Nehru and the other Indian leaders. The agreement was that the Indians would resist an imminent Japanese invasion in exchange for a measure of independence after the war was over.

Churchill, as you know, was quite keen on his India colony and wasn’t about to make major concessions. What happened when the cable reached Churchill for his approval was that he threatened to resign in Hopkins’ presence and Hopkins basically just off the top of his head said, “Mr. Prime Minister, Louis Johnson does not speak for the President. I can assure you.” Hopkins obviously knew Johnson DID speak for the President and he basically calmed Churchill down, they had that kind of relationship. Johnson had been undercut.

It’s sort of a fascinating incident. I got interested in pursuing it after the Johnson book came out.

Woven into your narrative are threads drawn from previously private sources. What were they, where and how did you find them?

Woven into your narrative are threads drawn from previously private sources. What were they, where and how did you find them?

The entrée was Diana Hopkins (Harry’s daughter by his second wife, Barbara). She lives in the DC area still. She’s in her 80s. Barbara died of cancer in 1937. When war in Europe broke out, Roosevelt asked Harry to live in the White House, in the Lincoln Room right down the hall from the President. Diana (then about 6 or 7) went too. She lived on the third floor and Mrs Roosevelt was her surrogate mother for about 3 years. Diana now lives out in Virginia and was a wonderful source that had not been interviewed for many years. She had observations about the workings of the White House when she was a child.

Her father remarried in 1942. So Diana had a stepmother and she was able to tell me a lot of things about the stepmother who in her own right was a fascinating character and no one had really written much about her either.

The way in which I got to Diana was through her daughter, Audrey, who is a lawyer (and I’m a Washington lawyer also) with another firm down the street from where I am. That was my entrée. Diana was not interested, it was difficult to get the first interview with her. I invited her and her daughter over to our house for a few drinks and she loosened up and we got along.

I did not find a cache of letters in the attic like the kind writers love to come upon, but I had some still living sources including Hopkins’ granddaughter who is a professor of history in Georgia, June Hopkins. She’s written a book focusing on Hopkins’ years as a social worker and is a descendent of Hopkins and his first wife – another fascinating character who was a social worker and a Jewish woman who Hopkins met when he was working in a settlement house in New York City.

Hopkins once quipped that he had “a leave of absence from death.” How true a word was spoken in that jest?

That was his quip when he was over in Russia with Stalin after Roosevelt died. He really did. He had a cancer operation after his second wife died of cancer in late 1937. Hopkins had an operation at the Mayo Clinic and they discovered cancer of the stomach. They removed, some say half, some say more than that, of his stomach and they reattached the plumbing. He didn’t ever function properly after that. Although, amazingly, the cancer did not recur and usually with stomach cancer it does.

So he survived but he was always having difficulty after that absorbing nutrients. Exactly what the medical problem was is still not precisely known. Several people have written about it – coeliac disease, allergic to some of the things people are allergic to today that they didn’t know about then. He didn’t take care of himself, he drank all the time. But he had injections, took liver extract and so on. One of the reasons Roosevelt invited him to live in the White House was that he was sickly and didn’t look so good. Of course Roosevelt wanted someone to be right there anyway.

After he got back from Tehran at the end of 1943, on New Year’s Day of 1944, he basically collapsed and had to go to the Mayo Clinic to recover. They said that he did not have a recurrence of cancer, but they did experiment with various ways to increase his intake of nutrients. He was in Mayo for 6 months before he came back and then he was way behind in terms of his relationship with Roosevelt. So it wasn’t until late 1944 that he restored his place at Roosevelt’s elbow. He missed out on a lot, but he actually saved Roosevelt from making some mistakes in late 1944. He recovered enough to go to Yalta (early 1945) but he spent the entire time in bed. He did get out of bed for the plenary sessions, but spent the rest of the time in bed.

Hopkins was witness to some of the biggest geopolitical decisions of his era – including the decision that keeping in with Churchill was more important than supporting the aspirations of Indian national leaders like Nehru; and the decision that keeping in with Stalin was more important than the independence of Eastern European or the Baltic States. These big decisions had big impacts on the lives and freedoms of millions of people. How conscious was Hopkins of the effect of those decisions?

Hopkins was witness to some of the biggest geopolitical decisions of his era – including the decision that keeping in with Churchill was more important than supporting the aspirations of Indian national leaders like Nehru; and the decision that keeping in with Stalin was more important than the independence of Eastern European or the Baltic States. These big decisions had big impacts on the lives and freedoms of millions of people. How conscious was Hopkins of the effect of those decisions?

It was all about winning the war. Even Churchill said he would court the devil – meaning Stalin – to win the war. The survival of civilization was at stake. Living with Roosevelt, he knew Roosevelt’s mind, if anyone knew Roosevelt’s mind. Hopkins was not immune from being seduced by Stalin, but I think he was more careful with Stalin than he was with Churchill. He had relationships with the Soviet Ambassadors Maisky (London) and Litvinov (Washington) as well as Molotov.

There was a guy named Joseph E. Davies who was a former Ambassador to the Soviet, very wealthy, living in Washington. Davies kept copious notes of dinners and meetings where he would call Hopkins over to his house and talk about how the Russians should be handled. Hopkins was in a position where he was speaking for the President on some pretty major issues, but i think he knew where the President stood on issues like the Baltics or Eastern Europe

During his lifetime (and afterwards) Hopkins was accused of profiting from public office. Why was he targeted for such character assassination and how did he afford to live in the manner to which he became accustomed?

Well first of all he was a proxy for Roosevelt and the right wing would use him as a way to criticise or challenge FDR.

Hopkins died with almost no money. When he resigned from the Truman administration in the summer of 1945 he went to New York. He had no money, neither did his 3rd wife Louise – she was working as a nurse in the war – but they were New Yorkers and they went house hunting. He was out of the administration and he was going to write a book. You would think they would get a two bedroom or one bedroom apartment but they ended up in a three or four storey town house on 5th Avenue overlooking Central Park. He hired a writer to help him write his books and he got all his papers assembled in that place.

I asked Diana, “How could they possibly afford that?” Diana said, “Well that was Averell Harriman [son of a railroad baron, Secretary of Commerce under Truman and later Governor of New York] who basically paid for that place.” Hopkins lived there and in late 1945 he really went downhill and had finally to go into a hospital. Louise was really connected in New York. She was friends with Jock Whitney who was a very eligible, very wealthy guy who started the Museum of Modern Art.

He leant her some of his paintings – very, very famous paintings. Hopkins got interested in art as he was in the hospital surrounded by some of these paintings that were leant to him, and which were around him when he died in 1946. Diana has one of those paintings out at her house in Virginia.

Insinuations were made about Hopkins’ ties to the Soviets. Did he, as is claimed, pass nuclear secrets and arrange for shipments of uranium to the USSR?

There were allegations that came from a guy called Major Jordan who claimed to have personally observed or overheard conversations between Hopkins and Air Force officers in which Hopkins authorised nuclear secrets to be put into boxes or briefcases and boarded onto planes in Montana bound for the Soviets. Major Jordan claims Hopkins authorised the disclosure of designs for building an atomic bomb to be shipped to the Soviets. It was very specific kinds of testimony in a congressional hearing. Of course the Republicans and the right wing gave those allegations creedence.

The cross-examination and report written after, in my judgement, completely vindicated Hopkins. By the time those hearings were held, Hopkins was dead. I have a book on my bookshelf that was written by Major Jordan after that and he makes the same allegations, but there’s no proof that designs were sent to the Soviet Union through authorisation from Hopkins.

The intercepts that the Russians got in Moscow through their spies were collected, translated and published after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When that book came out there was a flurry of newspaper articles and reports saying Hopkins was one of the sources of Soviet intelligence. It later turned out that the agent concerned was Laurence Duggan. The decrypts reveal that Duggan had worked for the Soviets before he fell to his death from his office in 1948. In my view, and most rational observers conclude too, Hopkins was not a Soviet spy.

Hopkins was brilliant one on one. He was the personal bridgehead between FDR, Churchill and Stalin. Yet what makes him fascinating in terms of his own legacy was his capacity to manipulate the bureaucratic machine. How do you write an engaging portrait of someone who’s very good in meetings and very good at paperwork?

Hopkins was brilliant one on one. He was the personal bridgehead between FDR, Churchill and Stalin. Yet what makes him fascinating in terms of his own legacy was his capacity to manipulate the bureaucratic machine. How do you write an engaging portrait of someone who’s very good in meetings and very good at paperwork?

You just put your finger on it. I think a lot of writers, including me, will just try and brush that off because it’s too difficult to write.

It’s very difficult to put meat on all those meetings. How did he really drive the New Deal programs that he did before the war started? The WPA, all of the jobs programs, the Federal Writers’ Project. His battles with Harold Ickes over who’s gonna get to build all the dams and the roads. He was on top and he remained on top. It was terribly difficult with infighting and backbiting.

The same thing happened with Lend-Lease which was his major bureaucratic responsibility, he got it up and going. How do you write about that without becoming dreadfully boring? Where were the key levers that he had to pull to make Lend-Lease work? Lend-Lease was not that effective but at least it gave everybody hope. You can write about that, about how much did it actually help Russia.

And how do you express his executive leadership? It’s much easier to talk about the night he spent with Churchill or the meeting he had with Stalin. Stalin is a character that has tremendous power so you can write about the tension between the two or with Churchill, but there are hundreds of bureaucrats, faceless bureaucrats who were going out and doing wonderful things.

Ultimate armchair general question – and without preempting your work on Marshall – if you had been in Roosevelt’s chair when he had to decide who was to lead the Normandy landings, which commander would you have picked – Marshall or Eisenhower?

If Marshall had expressed his preference to Roosevelt, Roosevelt would have given it to him. But he didn’t. He said, “It’s your decision and I’ll happily go along with whatever you want to do” – although he desperately wanted to do it. At that time Roosevelt was being heavily lobbied by the other Joint Chiefs and also by a bunch of congressmen. So if I were Roosevelt then I would have given it to Eisenhower, but if Marshall had said “I want it” and I were Roosevelt I’d have done it because he needed Marshall more than anything. It turned out to be the right decision but there was a huge lobbying campaign going on in Washington at that time behind Marshall’s back.

The key thing in the Hopkins book took place in July 1942 and that’s when Marshall was desperately trying to leverage the British into letting him invade Western Europe in 1943, or if they had to do an emergency thing he’d have put something together for ‘42. But he didn’t want them to go to North Africa. Hopkins was playing both sides of that thing and I think the significant moment in those meetings in London was when the British were saying, “We’re not going to do this. We want to go to North Africa.” Hopkins wrote on a note, “I’m terribly depressed.” Hopkins wanted to go the way the British were headed and so it was a moment when Hopkins was doing something to placate Marshall, and make him think he (Hopkins) was on the General’s side, but he really wasn’t. My editor at OUP emailed me when he got to that point in the book and he said, “That’s the essence of Hopkins.”

During the 6th Democratic debate for the 2016 Presidential nomination, Senator Bernie Sanders named Roosevelt and Churchill as leaders who would influence his decisions on foreign policy. In this important election cycle how important is that question and how impressed are you by Senator Sanders’ answer?

They always say it’s the most important election of our time. I think Roosevelt was one of our most admirable presidents. What’s really hard to understand is how difficult it must have been to work with Churchill. As the balance between the US armed forces and the British shifted, Churchill would just not let go of this peripheral strategy for defeating the Germans. How maddening it must have been for Hopkins, Marshall and everyone who had to deal with him. But certainly Churchill will always be so much of a profound figure from when he basically stood alone. That was his moment.

What should be playing on the stereo when we’re reading The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler?

A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square and As Time Goes By from Casablanca. It’s so interesting that on New Year’s Eve of 1942 they played the Casablanca movie at the White House and a week later they’re in Casablanca. If anyone ever writes a screenplay of Hopkins at that time, that would be something good to put in.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ? FOLLOW US ON TWITTER! FIND US ON FACEBOOK! OR SIGN UP TO OUR MAILING LIST!

First of all, we must contend with our name which, taken from the Ojibwa Indians, means ‘skunk.’ Then too, we used to be known as the Second City before LA went on steroids. We knew we were number two, not number one, and we were never allowed to forget it. That mind set fostered a certain perverse twist to our egos and our ids. Then there’s our weather. Let’s face it, when it’s nice, it’s really nice, but when it’s not, it’s horrible. And it’s horrible usually 6 months out of the year. That’s why we don’t act like carefree Californians. No – we need our coats, our scarves and our gloves. We don’t go naked into that good sunlight in January, and it marks us for life.

First of all, we must contend with our name which, taken from the Ojibwa Indians, means ‘skunk.’ Then too, we used to be known as the Second City before LA went on steroids. We knew we were number two, not number one, and we were never allowed to forget it. That mind set fostered a certain perverse twist to our egos and our ids. Then there’s our weather. Let’s face it, when it’s nice, it’s really nice, but when it’s not, it’s horrible. And it’s horrible usually 6 months out of the year. That’s why we don’t act like carefree Californians. No – we need our coats, our scarves and our gloves. We don’t go naked into that good sunlight in January, and it marks us for life. What’s the biggest licence (with Conan Doyle’s original formula) taken by any of the new writers?

What’s the biggest licence (with Conan Doyle’s original formula) taken by any of the new writers? Undershaw was briefly a hotel after Conan Doyle stopped living there, but has been vacant for most of the time since. Similarly (prior to its being listed by Historic Scotland) Liberton Bank House in Edinburgh – where the young Conan Doyle lived in the 1860s – faced demolition to make way for a fast food restaurant. Why have we been so neglectful of the bricks and mortar footprints of this most celebrated writer?

Undershaw was briefly a hotel after Conan Doyle stopped living there, but has been vacant for most of the time since. Similarly (prior to its being listed by Historic Scotland) Liberton Bank House in Edinburgh – where the young Conan Doyle lived in the 1860s – faced demolition to make way for a fast food restaurant. Why have we been so neglectful of the bricks and mortar footprints of this most celebrated writer?

Has Mr. Trump ever watched Local Hero? Did it make, or would it have made, any difference to his relationship with the holdout residents of Balmedie such as Michael Forbes?

Has Mr. Trump ever watched Local Hero? Did it make, or would it have made, any difference to his relationship with the holdout residents of Balmedie such as Michael Forbes? If any one decision lost John McCain the presidency it was arguably his choice of running mate. Have you any predictions about who Mr. Trump will ask to join his ticket and why? How does someone who projects a sense that he is irreplaceable and cannot be improved or balanced, begin to tackle that question?

If any one decision lost John McCain the presidency it was arguably his choice of running mate. Have you any predictions about who Mr. Trump will ask to join his ticket and why? How does someone who projects a sense that he is irreplaceable and cannot be improved or balanced, begin to tackle that question?

The key statesmen of Victoria’s reign appear through the course of the narrative, from Wellington via Peel to Gladstone and Disraeli. What light do the attempts throw on them and their policies?

The key statesmen of Victoria’s reign appear through the course of the narrative, from Wellington via Peel to Gladstone and Disraeli. What light do the attempts throw on them and their policies? What’s the most interesting place you’ve been in your search for Victoria’s assailants? Is there anything left to see outside the Public Records Office?

What’s the most interesting place you’ve been in your search for Victoria’s assailants? Is there anything left to see outside the Public Records Office?

Carson’s died owning about half a billion dollars. He was very much not in the 99%. Yet he opposed the Vietnam War and capital punishment, as well as favoring racial equality at a time when many Americans did not. Where would his inclinations be taking him in 2016? Would he look with any favour on Jim Webb’s possible run as an independent candidate in 2016?

Carson’s died owning about half a billion dollars. He was very much not in the 99%. Yet he opposed the Vietnam War and capital punishment, as well as favoring racial equality at a time when many Americans did not. Where would his inclinations be taking him in 2016? Would he look with any favour on Jim Webb’s possible run as an independent candidate in 2016? The book is the memoir of a bromance shared between you and Carson. Given his lack of other friends and family it may well be the final word on him done in depth by a contemporary. It’s a portrait of light and dark. How did you determine to walk the line between tell-all sensationalism and paying tribute to a one-time friend and mentor?

The book is the memoir of a bromance shared between you and Carson. Given his lack of other friends and family it may well be the final word on him done in depth by a contemporary. It’s a portrait of light and dark. How did you determine to walk the line between tell-all sensationalism and paying tribute to a one-time friend and mentor?

Brits like to think of themselves as great at pomp and pageantry. Are they as good at commemoration vs. celebration?

Brits like to think of themselves as great at pomp and pageantry. Are they as good at commemoration vs. celebration?

You must be logged in to post a comment.