“There were always a lot of fascists left in the woodwork, ready to continue the myth of a “glorious” twenty years of Fascism.”

WHAT: “Mussolini has rarely been taken seriously as a totalitarian dictator; Hitler and Stalin have always cast too long a shadow. But what was a negative judgement on the Duce, considered innocuous and ineffective, has begun to work to his advantage. As has occurred with many other European dictators, present-day popular memory of Mussolini is increasingly indulgent; in Italy and elsewhere he is remembered as a strong, decisive leader and people now speak of the ‘many good things’ done by the regime. After all, it is said, Mussolini was not like ‘the others’. Mussolini in Myth and Memory argues against this rehabilitation, documenting the inefficiencies, corruption, and violence of a highly repressive regime and exploding the myths of Fascist good government. “

WHO: University of Siena Professor Paul Corner is the Director of Italy’s Interuniversity Center for the Study of Twentieth-Century Totalitarian Regimes. He is an alumnus of St. John’s, Cambridge and St. Antony’s, Oxford. As well as his tenure at Siena, Paul has academically moonlighted as a visiting professor at the European University Institute, Fiesole; University of North Carolina; New York University; Columbia; and has been elected a permanent member of the Senior Common Room at St. Antony’s.

MORE? Here!

Why Mussolini in Myth and Memory: The First Totalitarian Dictator?

The book is a response to something that has been going on for decades but has become more accentuated in recent years – that is, the tendency to see Italian Fascism in a more positive light and to consider Mussolini to be a figure worthy of admiration. It is an attitude that can be summed up with the phrase used by the current Italian Foreign Minister, “Mussolini did many good things.” This indulgent attitude has developed around a whole series of myths about Italian Fascism – myths that often simply repeat what were in reality fascist propaganda slogans – and has been reinforced recently, of course, with the election of a post-fascist Prime Minister who consistently refuses to condemn the fascist experience. My book is an attempt to put the record straight and remind people about the reality of an inefficient, brutal, and corrupt regime. It is very often forgotten that Fascism cost Italy more than half a million lives.

Doctor Johnson did not quite say that “Nostalgia is the last refuge of the moron”, so why do intelligent people get themselves attracted to Mussolini’s myth and memory?

A good question, although I’m not sure that we are talking about intelligent people. One of the problems is pure ignorance about what Fascism represented. Many of my students knew a lot about the Risorgimento but nothing about Fascism. The schools simply hadn’t taught it; it was too sensitive a subject. That said, the attraction of the past is undoubtedly a reflection of dissatisfaction with the present. At the moment a lot of people are unhappy with their politicians, who seem unable to do anything about a long period of economic decline. In these circumstances, the idea that Mussolini was authoritative, decisive, and a man of direction is bound to appeal. He is seen as the man who wanted to make Italy great again and we know the attraction of that slogan.

A more in-depth answer to your question would be that, unlike Germany, Italy has never fully come to terms with its fascist past. After 1945, it seemed better to emphasize the heroic antifascist Resistance movement during the war, to look forward to reconstruction, and to brush twenty years of Fascism under the carpet. Very few fascists were put in prison and there was no real process of de-fascistization of the police or the state administration as there was in Germany. There were always a lot of fascists left in the woodwork, ready to continue the myth of a “glorious” twenty years of Fascism.

Mussolini is remembered in the same harsh breath as the totalitarian leaders of Spain and Germany. Could he ever have softened into an Atatürk?

Well, to do this, he would have to have stayed out of the war and for a Darwinian like Mussolini this was unthinkable. Remember that the key fascist slogan (apart from “Mussolini is always right”), was “Believe, obey, fight.” Had Mussolini stayed out of the war, there is a possibility that Fascism might have carried on as a more conventional authoritarian regime on the lines of Franco’ Spain. But you have to bear in mind that Fascism was already very unpopular within Italy in the late 1930’s and the regime had lost most of its totalitarian dynamism. And Mussolini was in rapid physical decline, with no capable successor in sight. Certainly, the regime still possessed the means of control, but it seems more likely that, in the light of an ever-worsening crisis of authority, far from softening, the fascists would have had to increase the levels of repression rather than reduce them.

Did Mussolini make the trains run on time?

Difficult to say because many of the records were destroyed during the war. Interviews with railway workers suggest that the mainline trains were generally on time, in part because timetables were adjusted to give trains adequate leeway, while less important local trains were as unreliable as they tend to be anywhere. However, this is a good example of a persistent myth which speaks of efficiency, “getting things done”, etc – all part of the “many good things” Mussolini is supposed to have done.

Could the Mussolini myth be seen as the inevitable result of the relative infancy of Italian statehood? A nation needs national myths and Mussolini is one of the few things that has happened to all of Italy since Risorgimento.

I wouldn’t quite put it like that but I think the long-term view has to be taken into account. One of the problems Italy has had in the past (and I’m speaking of Italy post-unification) and still has to some extent is the feeling that the country is not being given its due at the international level. It is a country that wants to count. This is very obvious at the moment with Meloni’s continual and rather unconvincing references to Italian “centrality” in many current international decisions. In some ways Fascism was a result of this sentiment.

Mussolini certainly represented international protagonism at a very high level – Munich 1938 is the most obvious example – and, even if his protagonism ended in national disaster, he is remembered for his strutting on the international stage. If you are an Italian what else do you look back to to bolster your sense of national pride? Of course, there are a lot very positive things to look back to but, for many people, this may not be too obvious.

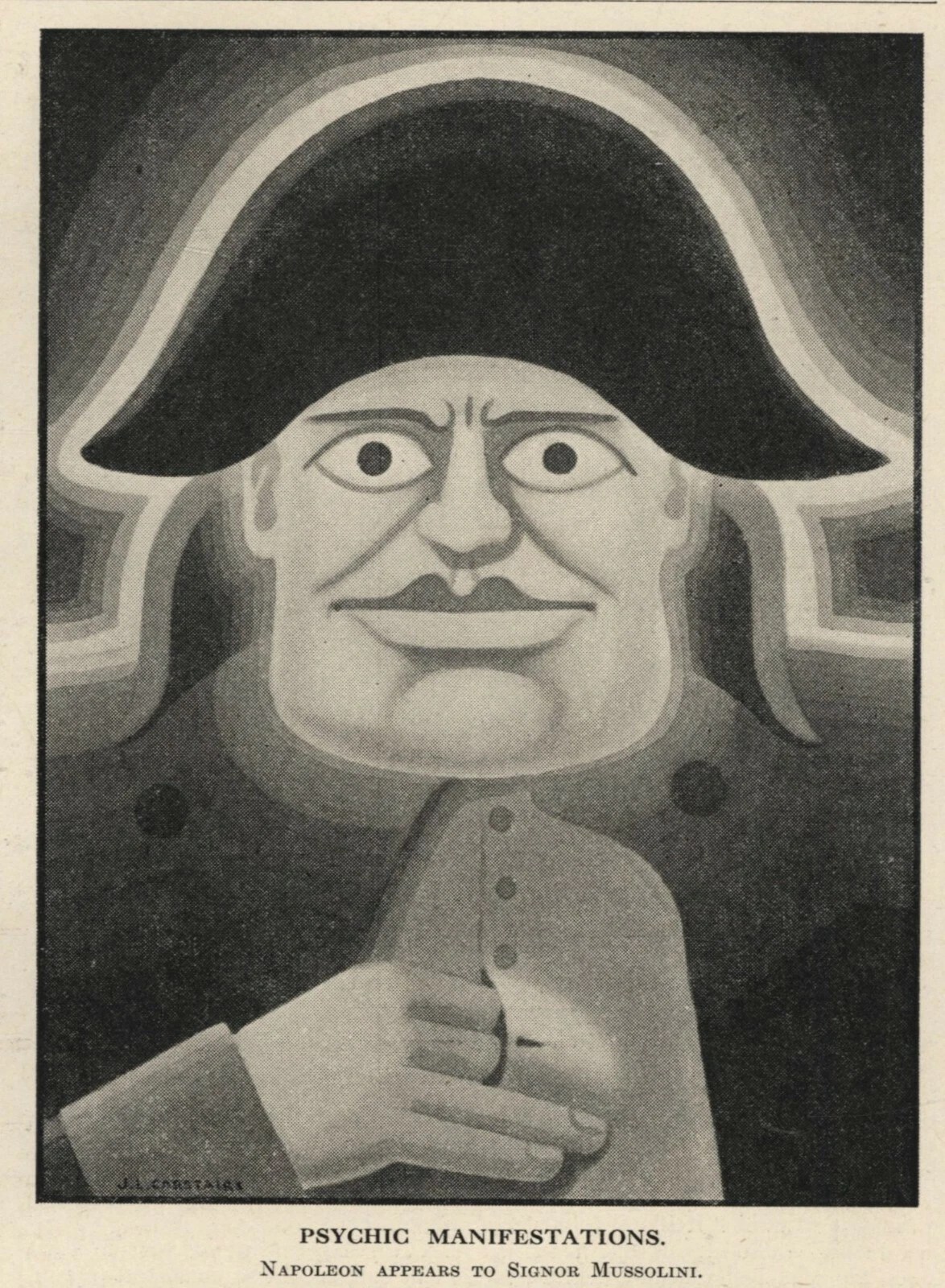

Mussolini’s play ‘Napoleon: The Hundred Days’ ends with a gesture from the defeated Emperor and an attendant snapping their sword in two with a sob. Do you think Mussolini meditated much about defeat before it happened to him? And what does the play’s presentation on the London stage, adapted by the eminent playwright John Drinkwater, say about international perceptions of Mussolini in 1932?

As is well known, up to the early ’30s Mussolini was widely admired at the international level. He was relatively young, very dynamic, and – perhaps most important for many observers – he had defeated the Italian communists. European and American political scientists and economists were very interested in the fascist “corporative model” which promised (but did not deliver) a way out of the international depression. For some observers, he was seen as the remedy for many of the stereotypical Italian weaknesses.

The admiration disappeared, of course, when he began to make friends with Hitler and, above all, when he attacked Ethiopia in late 1935. The Left was not taken in by appearances; it is enough to read the Manchester Guardian of the 1920’s to appreciate this.

Did he meditate about defeat? There is little indication that he did – until it was obvious that he had been defeated. After all, Fascism was supposed to last for a hundred years. But when defeat was evident, all he could do was blame the Italians for not coming up to fascist expectations. “Governing Italians is not so much difficult as pointless”, he is reportedto have said. It was the material the dictator had had to deal with that was at fault, not the dictator.

How do Roman Catholic thought leaders and senior clerics regard the Church’s relationship with Mussolini now, today in hindsight?

There’s no single view, of course. There are those who prefer to downplay the level of collaboration between Church and State and emphasize the role the Church played in providing an alternative to the fascist organizations. It is certainly true that many of the post-1945 leaders of the Christian Democracy were in some way protected by the Vatican during the regime. And there are those who suggest that the Church might have done more to oppose the regime, particularly after the introduction of the anti-Semitic Racial Laws in 1938. The shadow of the Holocaust and of “what the Pope knew” tends to condition much of the argument.

If you could step into a time machine, go back and meet Mussolini, WHEN would you want to encounter him and why? What would you ask him? What would you want to tell him?

I’ve never asked myself this question, possibly because I have never felt any desire to meet Mussolini. The young Mussolini is probably more interesting than the older man, who had come to believe in his own myth (one of his ministers said, in 1939, that talking to Mussolini was like addressing a statue). To talk to him in late 1914 about the war, his socialist values, and his reasons for abandoning socialism, could be interesting. This was a key moment in his life and to understand his reasoning would be important.

What would I tell him? I think I would have advised him to see a good psychiatrist before it was too late. He would not, of course, have listened.

Has Mussolini’s reputation managed to survive precisely because he was killed by partisans, rather than going through a Nuremberg-type process?

Possibly. For some his end resembled a martyrdom. There are historians who argue that the killing of Mussolini was done precisely to avoid letting him make his defence in a show trial. After all, he was a good speaker. This must remain uncertain. What is clear is – as I suggested above – the absence of any kind of Nuremberg trial in Italy allowed people to think that, in the end, Italians had been victims of Fascism rather than, in many cases, perpetrators. There was, therefore, no case of collective guilt to answer. This absence of any clear break with a criminal past has fostered the continuation of many fascist myths.

What are you currently working on?

I’m still working on various aspects of dictatorship, trying to spread the net beyond Italy. My most recent interest is in North Korea even if, as you can imagine, it is difficult to get hold of the documents, let alone read them! But it’s a fascinating story.

LIKE WHAT YOU JUST READ? FOLLOW US ON TWITTER! OR SIGN UP TO OUR MAILING LIST!

You must be logged in to post a comment.